By: Amber Smith

Several years after leaving Morgan State University with a major in physical education, Marcus Dumorin found himself grappling with repaying his $55,000 student loan debt while handling monthly obligations, including caring for his young daughter and sick mother.

His monthly payments had reached as high as $600, an insurmountable challenge given his salary and monthly expenses. Dumorin’s consistent pleas for a more affordable payment to his student loan servicer, Navient, were unsuccessful.

He was stuck. And stressed.

After requesting multiple forbearances, enduring a wage garnishment, and stumbling through a few repayment plans, Dumorin says he reached his breaking point.

“Something [had] to give,” he said. “It was just rough trying to dig myself out of that hole.”

One day, he saw a commercial from a student loan debt relief company, Premier Student Loan Center, claiming to lower borrowers’ balances by half. Dumorin believed he had found a solution.

Initially, it seemed too good to be true, but after talking to a representative, he decided to go for it. Soon after, his payments were reduced by more than 50 percent. Dumorin could finally see the light at the end of the tunnel.

There was only one problem. It was all a scam.

‘It All Comes Down to Wealth’

Dumorin’s story isn’t unique. It instead underscores the current state of the student loan debt crisis. Presently, more than 43.5 million Americans collectively carry a staggering $1.75 trillion in student loan debt, a burden that has become particularly challenging for a significant number of borrowers of all races and ages. However, Black borrowers are the most disproportionately affected.

Over the last 20 years, college tuition has outpaced students’ ability to pay for their education, thus making them more reliant on student loans and riddling them with thousands of dollars in debt. The expansion of the student loan system has broadened access to opportunities for communities historically excluded, but it has also yielded major consequences—a deepened racial wealth gap and Black borrowers, like Dumorin, becoming vulnerable prey for predatory lending practices.

Experts including Katherine Welbeck, Director of Advocacy at the Student Borrower Protection Center (SBPC), contend the student loan debt problem is primarily about who has access to wealth.

“We tell this story about the importance of education, and it is an important tool of social mobility,” said Welbeck. “But it really creates this double bind where you’re seeking a way out [and a way up] but when you don’t come from a household of wealth, you almost have to mortgage your future in order to access the next wave of opportunity.”

This certainly applies to students from communities of color as they hold less wealth than white households, but Black students, specifically, appear to bear more of the brunt. Black households have less parental and generational wealth and earn lower wages than white households, so they are more likely to pay for college using student loans. In fact, 90 percent of Black students use loans to pay for college, borrowing more than any other group. Data indicates they owe an average of $25,000 more than their white counterparts despite receiving less financial aid as a demographic. When borrowing from private student lenders, they often receive higher interest rates because they are considered higher credit risks.

Like many Black students, Dumorin didn’t come from a wealthy household. His mother was a single parent and unable to pay for his college education upfront. He hoped the few college football scholarships he received would help, but they fell short of covering the remaining balance. Taking out student loans was his only choice.

“I was offered a scholarship to [Bowie State University] but they even told me I’d have to apply for financial aid,” said Dumorin. “They would give me a certain amount of money, but the rest, either my parents would have to come up with, or [I’d] have to get it through financial aid. That didn’t make sense to me. You’re telling me I’m getting a scholarship but you’re not going to cover my tuition.”

He opted to enroll at Morgan State as a walk-on student athlete, financing his education through $35,000 in subsidized loans and $19,000 in unsubsidized loans. He would have borrowed more if he hadn’t withdrawn from school to take care of his daughter. Dumorin says he knew that upon leaving school without a degree and a high-paying salary, repaying the loans would present an uncertain challenge.

‘It feels like you’re constantly behind in the race’

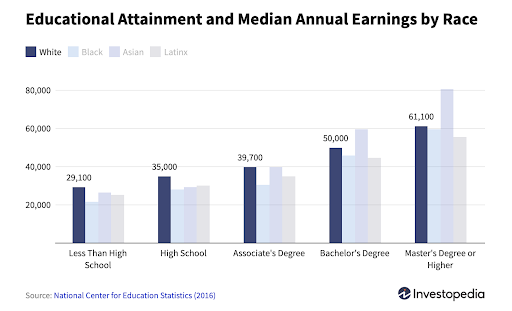

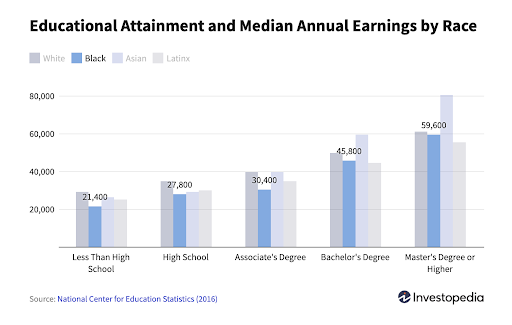

Dumorin represents the 40 percent of student loan borrowers, without a college degree, who struggle to pay off student loan debt. On the contrary, a college degree does not eliminate wealth and income gaps for Black college graduates, nor does it guarantee feasibility in paying off debt. Black workers still earn less than their white counterparts regardless of education level. Furthermore, white households currently have 10 times more wealth than Black households, while white college graduates have seven times more wealth than Black college graduates.

Taura Taylor, assistant professor of Sociology at Morehouse College says these inequalities make it difficult for the wealth gap to ever be closed.

“Even if I have a job today that’s paying $120,000, or even $200,000,” said Taylor. “I cannot make up for the trillions of dollars that [are] distributed predominantly among white Americans that [will] be transferred over multiple generations. It feels like you’re constantly behind in a race.”

Generational wealth gaps and income disparities already pose challenges for Black borrowers in repaying student loans. When combined with the burden of owing the highest monthly payments and being the second most likely demographic to face payments exceeding $250, it is nearly impossible for Black borrowers to get ahead. Moreover, Black college graduates often redirect their potential increased income to support their families. Research shows these factors often contribute to Black borrowers owing more than what they originally borrowed and why they’re more likely to default on their loans.

Such was the case for Dumorin. He was supporting his daughter, his ailing mother and himself on a $30,000 annual net salary, and yet, Navient believed he could afford to pay more than $250 a month. Even after applying for an income-driven repayment plan, the monthly bill was still out of his budget.

Unequal Burdens Podcast – The People Behind the Debt by Jaliya Monroe and Sabrina McCrear

Abdeena’s Story: Black Women and Student Loan Debt by Afia Barrie

‘It was all a lie’

Dumorin sought out the best solution at the time—a temporary postponement of loan payments, or a forbearance plan. He requested them multiple times, in fact. While he managed to experience some relief during those periods, his loans were steadily accumulating interest at 5 percent.

Some student borrower protection advocates allege loan servicers use forbearance and income-driven payment (IDR) plans to trick borrowers into prolonging the life of their loans. Black borrowers are often the targets of these tactics as they have no other option but to turn to IDR plans, and have the highest forbearance rates than any other group.

The Education Trust, an advocacy organization, argues that IDR and forbearance plans harm Black borrowers rather than help, citing increased loan balances from accrued interest and failures to cancel loans even after meeting repayment plan terms.

In a 2022 article, they reported, “Servicers are failing to effectively track payments and maintain accurate records. Documents from the Department of Education show that loan servicers have even purposely steered borrowers into forbearance instead of IDR plans. This hurts borrowers with low income because the time spent in forbearance does not count towards cancellation, and loan interest continues to accumulate.”

Dumorin’s student loan servicer, Navient was accused of imploring this exact predatory tactic. A 2017 lawsuit filed by Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro claimed Navient steered borrowers into further debt by encouraging them to apply for forbearance plans all the while still accruing interest. The lawsuit also alleged they pushed risky, subprime loans to students who attended for-profit schools knowing they would have difficulty repaying the money.

Although Navient denied any wrongdoing, they settled the lawsuit for $1.85 billion, with most going toward private student loan cancellation and the rest in restitution to almost 60,000 borrowers. After the lawsuit, they announced their departure from the federal student loan servicer market.

Multiple forbearances were exactly what led to Dumorin’s payments ballooning to nearly $600 monthly. If he was struggling to afford the monthly payments before the forbearances, then there was no way he could afford anything higher.

“It just wasn’t realistic,” he said. “At the time, I had my own [apartment and] I had my daughter. My mom was getting sicker, so I had to contribute to her household and mine. If I paid that bill, I [was not] going to be able to pay my rent, pay my car note, help my mom [as] she needs me to, or take care of my daughter.”

After several missed payments, he defaulted on his loans and his loan servicer subsequently filed to garnish his wages. Instead of the $600 monthly payments they initially asked for, they were garnishing $800 a month from his paycheck—almost 32 percent of his monthly net income.

“I heard of them garnishing people’s wages. I just didn’t think it would happen to me,” he said.

The wage garnishment made his financial situation even more dire. Dumorin says he was unable to fully support his family and had no choice but to apply for public assistance, a common reality for many Black borrowers.

He was desperate for a way out at that point. Likely why he was eager to believe Premier Student Loan Center’s promise of relief.

“They seemed really legit,” he said. “They even told me they were backed by the Better Business Bureau. So, I said, ‘This sounds really good.’”

Dumorin said the company promised they could cut his student loan balance in half and reduce the length of his loan terms. At their request, he submitted several loan documents and gave them access to his online student loan servicer account. The company even went as far as sending him email confirmation showing his loan balance had dropped to $19,000.

There was no reason for him to question the payment plan’s legitimacy, especially considering he never received any late payment or default notices from his student loan servicer.

“They were sending me receipts of my monthly payments and telling me how much of my balance I had left,” he said. “It turns out they were just using my account information to apply for [forbearances] on my behalf.”

For more than three years, Dumorin made consistent monthly payments to Premier thinking he was finally digging himself out of a hole. In reality, his loans were accruing interest the entire time. He didn’t discover the truth until early 2022.

“It wasn’t until I received a letter from the [Consumer Financial Protection Bureau] (CFPB) saying that if you participated in this repayment program, then you’ve been [defrauded],” said Dumorin. “It was all a lie.”

‘Predatory Inclusion’

These forms of predatory and deceptive practices fall under what Welbeck calls predatory inclusion, also known as reverse redlining. It occurs when institutions such as payday lenders, car title lenders, and check-cashers offer services and goods to marginalized groups who were historically excluded.

They market to these specific groups promising access to financial stability and opportunity through lending products, higher education, or job training; yet tack on exorbitantly high interest rates, enforce unreasonable repayment plans, or fail to disclose information regarding requirements, loan consolidation, and cancellation.

In Premier’s case, they used deceptive and predatory marketing tactics to prey on vulnerable borrowers, promising to reduce balances, but failing to disclose that they had no authority and capability.

In October 2019, the CFPB, along with the states of California, North Carolina and Minnesota, filed a class-action lawsuit against Premier for using deceptive practices against borrowers, claiming the company collected more than $95 million in payments. Despite the lawsuit filing, they were still collecting payments from Dumorin.

As part of the lawsuit’s resolution, Premier was ordered three years later to pay $95 million in compensation to more than 85,000 borrowers impacted by the scam. Dumorin says although he paid Premier more than $6,000, he only received $80 from the compensation fund.

“I was highly upset, [asking], ‘Why did I do that?,’” he said. “I thought I was helping myself get out of debt, thought I was making the right move for myself in the future. I was kicking myself. How are they allowed to do this?”

In May of this year, a federal judge ordered Premier to pay an additional $147.9 million in penalties to the CFPB and the three plaintiff states.

Lending and for-profit educational institutions are often accused of engaging in predatory inclusion. Once again, Black communities and other communities of color are often the targets of these tactics.

“They’re banking on these students not knowing that they’re predatory, on not understanding that their only goal is to extrapolate wealth,” said Welbeck. “What they don’t tell you is they’ll make [students] reach the top end of their federal lending limits, but they’ll also tack on their own private lending products.”

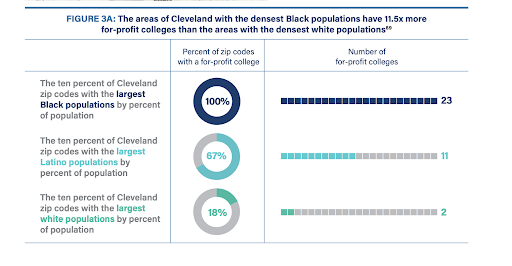

In a 2021 research report, the SBPC found that for-profit institutions intentionally set up shop in Black and Latino communities and recruit students with the promise of higher education and job training. Of the Black communities surveyed throughout Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, and Milwaukee, they report Black communities, nationally, are more than 75 percent more likely to have a for-profit school than white communities.

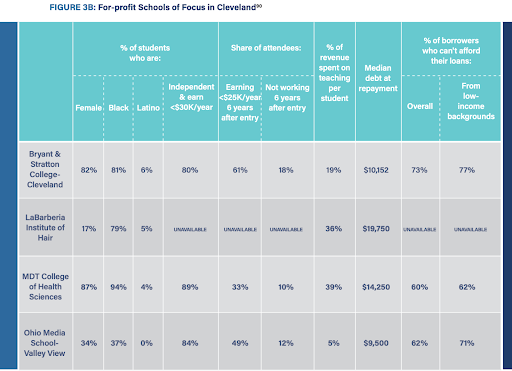

Their research highlights institutions like Bryant & Stratton College’s Cleveland campus. The college, which recently converted to a nonprofit institution, enrolls approximately 81 percent Black students. The SBPC found that the school leaves its students with more than $10,000 in federal loans while more than 60 percent of students are still earning less than $25,000 annually well over six years after entering the program.

The SBPC said, “Fewer than 20 cents of every dollar that this school spends is on teaching, and over 70 percent of borrowers who attend this school are making no progress paying down their loans.”

“In too many cases, borrowers attending for-profit colleges are far worse off than if they had never entered higher education at all.”

Other for-profit institutions have come under fire for imploring predatory inclusion tactics.

The National Student Legal Defense Network filed a class-action lawsuit against Walden University last year, accusing the institution of targeting Black and female students for its Doctoral of Business Administration program through tailored and predatory marketing strategies. Almost 41 percent of Walden’s doctoral students are Black, and 77 percent are female.

“Walden lured Black students and women into their doctoral programs under the pretense of a social justice mission, then essentially held their degrees hostage for ransom. It’s a particularly egregious scheme, even by predatory college standards,” said Student Defense President Aaron Ament in a press release.

The lawsuit claims Walden focused 90 percent of its 2020 local advertising budget on communities with a predominantly Black population. It also alleges the university misrepresented its program requirements and then made students complete additional coursework previously not advertised, thus extending the length of the program, inflating tuition costs and forcing students to take on more student loan debt.

The organization estimates Walden overcharged its students by $28.5 million and is responsible for more than $800 million in federal student loans in the 2019 academic year alone.

‘Public Policy Failures’

There are many reasons as to why the student lending system has evolved into its current state. Some experts cite greed and capitalism, and while those may be factors, others point to public policy. More specifically, they point out how public policy throughout history has created lasting systemic inequalities.

“The fact that we treat higher education as something that is financed through debt, and not a public good, is a public policy failure at the larger level,” said Welbeck. “Then, you distill that down and think about how it disproportionately affects Black and Latino borrowers. Why do we even have a racial wealth gap? Again, public policy failures. Many of these were intentional public policies but they were still public policy failures.”

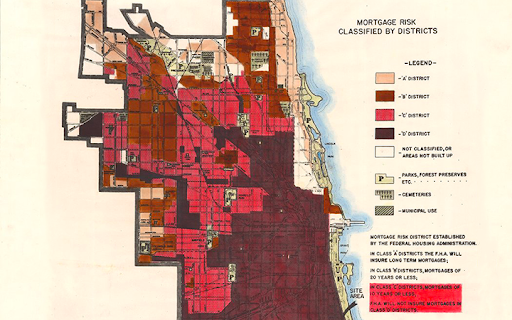

Welbeck referenced redlining and its trickle-down impact. The racially discriminatory practice used color-coded mapping to label Black communities as too risky for lending and economic investment. For decades, this covert (or often not covert) practice went unchecked by public policy. In turn, it denied millions of Black Americans access to homeownership, equitable credit, and other resources, ultimately hindering their opportunities for wealth building. Between higher interest rates, Black borrowers’ reliance on student loans, and predatory for-profit schools’ marketability in Black communities, the impact now permeates throughout the student lending system.

Brittani Williams, an inaugural fellow for Howard University’s Center for HBCU Research Leadership and Policy and a senior policy analyst for The Education Trust, also points to racially systemic public policies as a cause.

“We cannot have this conversation without recognizing how race plays a part in the student loan debt crisis and [in these policies],” said Williams. “While these policies may not explicitly call out a particular race, there are systemic inequities that have been perpetuated through several policies historically across the nation.”

If public policies are what caused the current student loan debt crisis for Black borrowers, then it is public policies that will fix it, at least that is what student borrower protection advocates argue.

Various advocates have proposed numerous solutions including stronger fair lending oversight within the student loan market, accountability for institutions that violate discrimination and fair lending policies, elimination of interest rates on federal loans, increases to Pell Grants, and IDR plan reforms. Ultimately, most advocacy groups call for the total cancellation of student loan debt.

However, Williams, at the Education Trust who is also a student loan borrower, personally believes student loan debt cancellation will not completely fix the problem.

“I agree with people who say to cancel all [student loan] debt, but for me, it’s a ‘yes, and’” she said. “There is more work to be done. It’s important if we have this conversation, especially for the Black community, to discuss the issue of college affordability.”

“Canceling student loan debt will help current loan borrowers, but what about future borrowers? We need to also address the issue of college affordability. College is simply not affordable for all now.”

As for Dumorin, he is still reeling from being scammed by Premier Student Loan Center.

The student loan moratorium during the COVID-19 pandemic offered him more than a year of reprieve but now it is time for him to resume his payments, just like millions of other borrowers.

The worst part, he said, is that he is back where he started.

In September, his new loan servicer, Nelnet sent him a letter that his payments would resume in October. He was shocked to learn his balance is still close to $55,000.

“They know I was scammed. I thought they would have at least forgiven the amount that I paid to Premier, but they didn’t,” he said. “They didn’t even forgive the interest.”

There is some upside for Dumorin. His monthly payments are no longer $600—they are $500.

Dumorin said he applied for an income-driven payment plan with the new servicer and is currently waiting to learn if his payments will be adjusted. In the meantime, his payments are paused.

“I’m in a better financial situation now, so I can afford to pay more than I previously could. If they can’t lower the payment, I’ll just have to figure it out. I just want to pay off this debt and be done.”

Research by Aniya Greene and Tchericka Petit-Frere