By Tai Spears

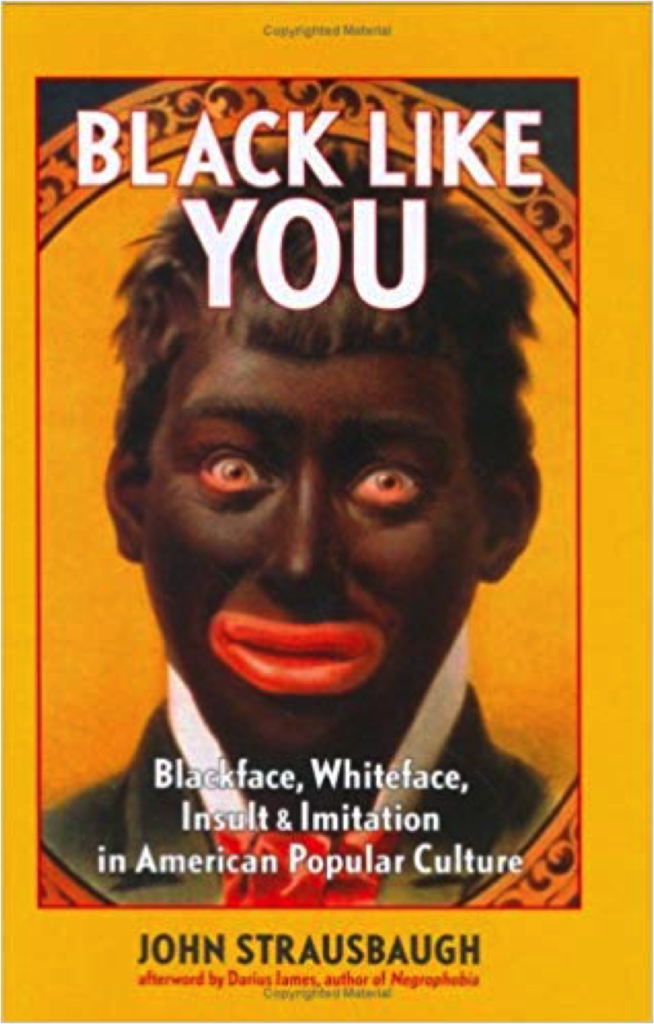

A recent series of scandals, and the backlash and public scrutiny that follow, has brought the issue of “blackface” to the forefront. Although it has become a trending topic of controversy, the use of blackface is nothing new in American culture. Its reemergence in the news, however, has reminded many of the painful history it represents.

Blackface is defined by Webster’s Dictionary as “black makeup worn in a caricature of the appearance of a black person,” yet its symbolism has become much more complicated over the past decades.

Blackface originated as an ancient European theatrical device brought to America by Europeans. At the time, the use of blackface didn’t signify race but instead the underlying color symbolism in Europe. For Europeans, it seemed fairly easy to explain, white meant light, daytime, good and safety while black meant night, darkness, bad and danger, according to an article by Robert C. Toll in American Heritage magazine. What once seemed harmless in the eyes of Europeans took on a much more negative connotation as it moved into America.

In the U.S., the slave nation, where whiteness or blackness is of high importance for the quality of life and social standing, blackface took on a very different meaning. Blackface in America made its landing during the 1820s, on minstrel show stages. Minstrel shows were popular comedic performances that depicted people of African descent. Many of these performers were white men who had grown up poor and often Irish in the North. Their acts imitated blacks who lived in ghettos on the Lower East Side of New York City, just as they did. Blackface quickly became a way for people who were white, but not accepted by whites, to say, “No, we’re white because we put on the blackface,” according to an article this month on Vox.com.

Blackface performances in America commonly characterized blacks as lazy, ignorant, superstitious, hyper-sexual individuals who were cowardly and prone to thievery. There was always, even in its earliest days, a racist tone to blackface, but there was also an underlying sense that black people were cool, the Vox article said. However, as blackface became mainstream and commercialized around 1840, and particularly after the Civil War, its use grew to be much crueler, much uglier and more about mockery.

By the 1960s, blackface had become one of the few taboos in American culture along with the n-word and the swastika. It wasn’t until the 1980s, after blackface had died out, that there was a revival of it on college campuses all across the country. In a recent article, the Washington Post reported that the meaning of blackface was relatively the same but the intention was to be a direct reaction to the effort to diversify universities at the time, by opening them up to people of color.

Such acts of racism were brought to light in recent weeks after Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam’s old college yearbook page surfaced online. The page included a photo of two men, one in blackface and the other in a Ku Klux Klan costume, sparking outrage across the country. Northam, who took office in January 2018, has ignored calls for his resignation.