By Samantha Chaney

Every election season we are given a list of reasons why we should exercise our right to vote. We are told that voting is the opportunity to demand change and choosing not to vote is a choice to silence your voice. There has been a call to action this year echoing across the nation, urging Americans to vote like their lives depend on it. Unfortunately, many Americans who have been convicted of a felony will miss that call. With restrictions and regulations varying from state to state, many are unsure where they stand when it comes to having the legal right to vote at all.

“They didn’t really go deep into everything that goes along with the felony, but I know I can’t vote. Until I’m off probation, I’m a felon. That’s just how it is,” said Dushawn, a resident and college student in Arizona who asked to be identified by his middle name only. “I got three years’ probation with an undesignated felony. Once I get through that, the judge can make it a misdemeanor.”

Dushawn was convicted of a felony in 2019 and was not required to serve any time in prison. However, he is concerned that because Arizona is a “red state,” the possibility of remaining a felon and never having his rights restored is higher than in other states.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in Arizona, those who have been convicted of one felony conviction will automatically regain their civil rights upon absolute discharge from imprisonment or completion of all aspects of their probation. If you have multiple felony convictions and were incarcerated, you must wait two years from your date of absolute discharge to apply for your rights to be restored. Your rights restoration application must be submitted to the court where you were sentenced (or, if your conviction was in federal court, to the presiding judge of the Superior Court in the county where you now reside).

Disenfranchisement due to a felony conviction disproportionately affects African Americans. The Law Dictionary reports that other rights convicted felons lose in the U.S., which varies by state, include “traveling abroad, the right to bear arms or own guns, jury service, employment in certain fields, public social benefits and housing, parental benefits.”

Among those eligible to vote, Black turnout reached a record high of 66.6 percent in 2012, then dropped in 2016 for the first time in a presidential election in 20 years, hitting 59.6 percent, the Pew Research Center said. Still, both candidates, President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden, know how important the support of the Black community is in winning this year’s election.

But neither has convinced some citizens. Said Dushawn, “Even if I could vote, I probably wouldn’t. Not in this year’s presidential election at least. Both choices aren’t good to me, and I know they aren’t going to do anything to help me or my situation.”

Besides Arizona, Florida is another state where those who have previously been convicted of a felony must jump through many hoops to restore their rights. In addition to completing probation, in both states, previously convicted felons must pay court-ordered fines or restitution before their right to vote will be restored. In September, billionaire and former New York Mayor Mike Bloomberg tweeted, “The right to vote is fundamental to our democracy and no American should be denied that right” after helping raise $16 million to pay the fines and restitution of over 30,000 Florida felons so that they could vote in the 2020 election.

In 2016, The Sentencing Project reported that the state of Florida alone accounted for more than a quarter (27 percent) of the disenfranchised population nationally, and its nearly 1.5 million individuals disenfranchised post-sentence account for nearly half (48 percent) of the national total. It also reported that one in five African Americans were disenfranchised, representing 21 percent of Florida’s disenfranchised population.

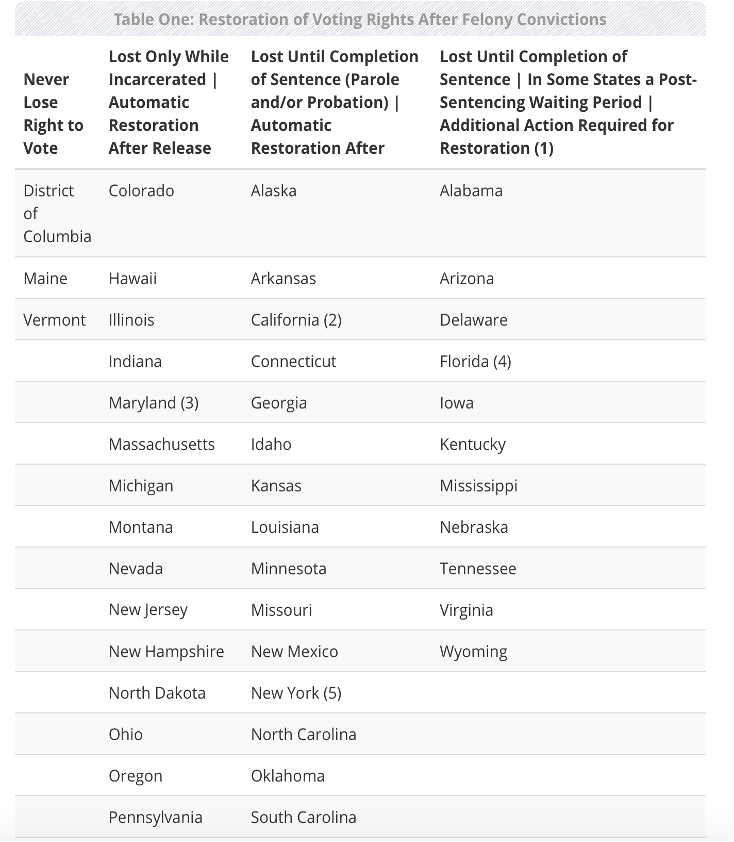

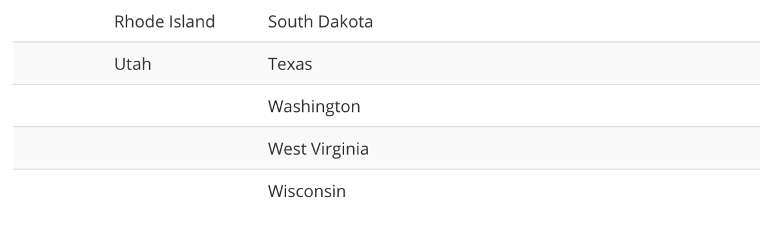

The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) reports that in 11 states, American citizens who have been convicted of a felony permanently lose their right to vote. In 16 states felons lose their voting rights only while incarcerated, while in 21 other states felons are temporarily restricted from voting and their right to vote is restored after they have served their time and completed their probation or parole period. NCSL adds, “In the District of Columbia, Maine and Vermont, felons never lose their right to vote, even while they are incarcerated.”

This table shows the restoration process for voting rights after felony convictions:

Chart courtesy of National Conference of State Legislatures

In Minneapolis, Manu Lewis, founder of ManUcan Consulting, knows all about the process of restoring the rights of a previously convicted felon. “I’ve been an example because I’ve had my rights taken away when I had a felony,” he said. “So it was going through the process of doing my homework and finding out in Minneapolis, Minnesota, when the time limit was up. This was during the Obama election.”

After serving time in prison in Georgia, Lewis moved to Minnesota and became an advocate for restorative justice. He began involving himself in organizations in the Minneapolis community that got Black voters registered to vote. He said, “Restorative justice community action is just one of the many organizations that I am a part of. We’re trying to get the community to be able to restore its values. We want to keep them a part of the community but give them something better to do.”

The Minnesota Department of Human Rights reports, “63,000 Minnesotans are unable to vote due to a felony conviction. Three out of four of them aren’t in prison — they live in the community, pay taxes and have families. But because they are still on probation or parole for something they may have done many years ago, they are disenfranchised.”

According to Restore Your Vote, a project of the Campaign Legal Center, “up to 18 million Americans with past convictions can vote RIGHT NOW – they just don’t know it – because the felony disenfranchisement laws in every state can be confusing.”

When asked why it is so important for Black people, and especially Black people who have previously been convicted of a felony to exercise their right to vote, Lewis responded, “This is a perfect time to get engaged and show what we want to actually see in our own community, instead of waiting on someone else to come save us.”