By Nancy Vu

As the number of people infected with COVID-19 passes 4.7 million, cases in the United States have reached more than 1.4 million with at least 89,000 deaths as of May 17. Government and health officials seeking to “flatten the curve” of infection and deaths have ordered unprecedented social distancing measures that shut down schools and businesses across much of the nation, resulting in 316 million people staying home and a severe disruption to the economy. As the country begins to reopen after several weeks, it begs the question: Why hasn’t the United States reacted with such extreme measures to other pandemics and epidemics?

It’s not like there haven’t been other deadly outbreaks. In this article, we examine the country’s response in those cases. To provide context, a pandemic is defined as “the worldwide spread of a new disease,” according to the World Health Organization. In contrast, an epidemic is the emergence of a disease in a specific community or region.

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

After first being discovered in Asia in February 2003, this form of the coronavirus had spread to over a dozen countries in North America, South America, Europe and Asia in 2003. Within a matter of five to six months, the virus was contained through various measures, but the most extreme measures were taken in mainland China, according to a study done by the National Center for Biotechnology. Large numbers of schools, government offices and universities were shut down, and quarantines were enforced to further prevent the spread of the disease. In the United States, travel advisories were issued to warn travelers against visiting SARS-affected countries. The Centers for Disease Control decided that quarantine was only necessary with individuals that carried the disease, since persons with SARS were only contagious when they became symptomatic. The novel coronavirus that the world is experiencing currently has proven to be more contagious, spreading when persons are asymptomatic and are unaware that they are carriers.

In an interview with Dr. David M. Morens, the senior advisor to the director of the National Institutes of Health, he said that SARS did not evolve into a pandemic because measures were taken ahead of time to contain the virus at its point of origin, Hong Kong. However, with the case of COVID-19, the international community was notified too late.

“Wuhan is an internal city,” said Morens. “When a problem happens in Hong Kong, everybody all over the world knows about it. When a problem happens in Wuhan, the same problem or a similar problem, nobody knows about it… the problem can occur and spread before anybody thinks, ‘Hmm, maybe we’re at risk.’”

Ultimately, the United States did not need to utilize the same extreme measures being used to counteract COVID-19 because most cases of SARS were found and contained in Asia. At the end of the pandemic, the U.S. had reported eight SARS infections, with zero deaths. Globally, however, 8,098 people were infected with the disease, with 774 deaths.

Here is a timeline of actions taken by the CDC: https://www.cdc.gov/about/history/sars/timeline.htm

H1N1

The H1N1 swine flu proved to be more contagious than SARS, infecting 60.8 million people in the U.S., and a whopping 700 million worldwide. Originating in Mexico in 2009, an estimated 600,000 people had died from the virus globally, but ultimately the mortality rate proved to be just 0.02 percent. In contrast, COVID-19 has a mortality rate that is 225 times stronger than H1N1, with the rate being evaluated as 4.5%. The difference is due to the population having “herd immunity,” which is when a significant chunk of the populace is immune to the disease by contracting the virus or getting vaccinated.

| Epidemic/ Pandemic | R Naught (How contagious it is) | Mortality Rate (%) | U.S. Cases | U.S. Deaths |

| COVID-19 | 2 | 4.5 | 1.48 million* | 89,562* |

| SARS | 2-5 | 10 | 8 | 0 |

| 2009 H1N1 | 1.5 | 0.02 | 60.8 million | 12,469 |

| Ebola | 2 | >50 | 11 | 2 |

| Seasonal Flu (Oct. 2019-April 2020) | 1.3 | 0.1 | 39 million-46 million | 24,000-62,000 |

| 1918 Spanish flu | 1.8 | 2.5 | Unclear | 675,000 |

| 1957 Flu | 1.7 | 0.6 | Unclear | 116,000 |

| Measles (before 1963 vaccine) | 12-18 | Unclear | 4 million every year | 400-500 |

*as of May 17, 2020, according to Johns Hopkins University

“With H1N1, there were people who had immunity that was pre-existing, probably because they were exposed to the 1918 flu strain, believe it or not,” said Abigail Carlson, assistant professor of medicine at Washington University in St. Louis. “But essentially, people born before the 1950s in the last influenza pandemic already had some preexisting immunity.”

Still, people born after the 1950s were left vulnerable against this new strain of H1N1, which prompted the government to take action. However, much of the U.S.’s decisions to respond to the virus received mixed reviews. On one hand, the outbreak of the virus showed various weaknesses in the American health system: obsolete vaccine technology that ended up underproducing the number of vaccines that were expected (the government predicted in the summer of 2009 that they would have access to 160 million doses, but instead ended up with less than 30 million), overreliance on foreign factories to produce the needed vaccines, and hospitals being pushed to the brink of their resources for what was deemed a mild epidemic. The U.S. ignored advice to close the Mexican border and to shut down schools, did not evenly distribute the antiviral Tamiflu to proactively counteract H1N1, and chose not to stretch the first 25 million vaccine doses into 100 million (which was made possible by chemical “boosters”) in fear of scaring the public in the midst of the 2009 antivaccine movement, according to a New York Times article. Other mistakes included not cooperating with Mexico soon enough, and not distributing vaccines strategically to areas or populations deemed more essential.

However, Dr. Gerald W. Parker Jr., who serves as an ex officio member of the Bipartisan Commission on Biodefense, said that numerous obstacles that the U.S. government faced during 2009 were structural. For example, Parker said the United States embarked on “aggressive research and development effort starting in 2006 to try and change the industry from egg based to cell based manufacturing technology,” which would mass manufacture vaccines quicker and in larger numbers. Ultimately, however, they were unable to shift industries toward the new technology.

“It proved to be technologically much more difficult than we anticipated,” said Parker. “It was still the most successful surge manufacturing campaign in history.”

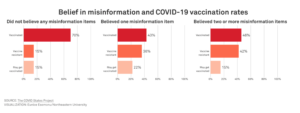

One major win that resulted from the H1N1 pandemic was that health organizations, such as the CDC and WHO, were able to mitigate the damage misinformation might have had by responding promptly to rumors and holding regular news conferences, resulting in little impact to the economy.

Ultimately, however, the deaths that resulted from the H1N1 outbreak were far greater than the SARS outbreak, with 12,469 deaths in the U.S. Whether or not this was a result of the U.S.’s conservative measures is a relevant point to consider, and in relation to today’s crisis, one must to ask: Are today’s current measures in response to the mistakes made in 2009-2010?

According to Dr. Morens of the NIH, the measures being taken today are completely separate from 2009, which was a relatively mild pandemic.

“This is a different situation, and the mistakes we made now are relevant to the now situation, and not the 2009 situation,” said Morens. “What happened in 2009 in terms of fatality was not much worse than what happened every year since 1918, so it wasn’t that big of a deal.”

Ebola

Formerly known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever, this virus has been around since 1976, and has recurred over the last 44 years. Although Ebola has the same contagion level as the coronavirus (their R naught level, which measures how contagious an infectious disease is, is around 2), it is far deadlier, with a mortality rate exceeding 50%. This is due to the difference in inoculum levels, or, “the amount of a virus that you would need in order to really get sick and for it to get really out of control in your body,” according to Carlson.

During the 2014-2016 outbreak in West Africa, much of the U.S. efforts were toward containing the virus at its point of origin. The country committed more than $350 million toward fighting the outbreak, with the CDC deploying personnel and resources to help mitigate the outbreak.

Overall, 11 people in the United States had tested positive for Ebola and were treated, with two fatalities. The U.S. was able to contain the virus at its epicenter, with most of the deaths reported in countries like Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. In total, there were 28,616 cases of the Ebola virus worldwide, and a total of 11,361 deaths.

Influenza

Seasonal flu

There have been various comparisons made between COVID-19 and the seasonal flu. Both are respiratory diseases that cause similar symptoms (fever, cough, headaches). However, there are some key differences, which may have influenced the U.S. decision to up the ante when COVID-19 appeared. Not only does the novel coronavirus appear to be more contagious, but the estimated mortality rate at 4.5% appears to be 45 times deadlier than the flu.

However, this current pandemic bears a major resemblance to past flu pandemics, such as the 1918 Spanish Flu and the 1957 H2N2 Flu.

1918 Spanish Flu

The 1918 Spanish Flu was one of the most horrific pandemics of the 20th century, killing at least 50 million worldwide, with 675,000 of these deaths occurring in the United States. While the origin of the virus is unknown, the virus was caused by an H1N1 virus found in domestic and wild birds. Statistically speaking, COVID-19 is more contagious than the Spanish flu, and if the coronavirus’s mortality rate continues on its current trajectory, it could be considered twice as deadly. However, social distancing isn’t a new idea. Many of the same measures that are being taken today were seen during the 1918 pandemic.

According to Robert A. Clark’s Business Continuity and Pandemic Threat, St. Louis was the first city to introduce the term “social distancing,” mandating the closure of schools and public gatherings, and the extreme regulation of public transportation systems. This seemed to have worked, as St. Louis “recorded the lowest number of influenza cases for all major cities in the United States.” Cities in Minnesota, such as Minneapolis and St. Paul, were the first to order civilians to wear mandatory face masks, along with employing more stringent sanitation laws. Other cities began to follow, including New York, San Francisco and Philadelphia.

Although it’s been more than a century since the 1918 pandemic and technology has advanced, history has come to repeat itself.

1957 Flu Pandemic

Originating in Singapore, the H2N2 virus pandemic was first reported in 1957. Killing at least 1.1 million people worldwide, the 1957 flu proved to be just as contagious as the coronavirus, with an R naught of 1.7, resulting in 25% of the population becoming infected. However, COVID-19’s potential mortality rate seems to be on a deadlier trajectory. As a result, responses to the 1957 flu pandemic were relatively mild.

The 1957 pandemic marked the beginning of an era. According to Morens, “1957 was the first pandemic in which we could isolate a virus and study it scientifically, and so a huge amount was learned, or began to be learned.”

Measles

A highly contagious infectious disease caused by the rubeola virus, measles used to be common before a vaccine was introduced in the early 1960s. While it was first recorded in the 7th century, it wasn’t until 1912 that measles become a “nationally notifiable disease in the U.S., requiring U.S. healthcare providers and laboratories to report all diagnosed cases,” according to the CDC. As a result, calculating the mortality rate before 1912 would prove to be difficult. In the decade after, however, the CDC reports that an estimated 6,000 deaths occurred as a result of measles each year. Children younger than 5 years of age along with adults older than 20 years were more likely to suffer from complications of the disease.

Although measles is extremely contagious with an R naught of 12 to 18, the mortality rate is hard to calculate because of the lack of reported cases. In the decade before the vaccine was introduced, measles was so prevalent that nearly all children would be infected with the disease, and many of these cases would not be officially reported. On average, reported cases would amount to 3 million to 4 million per year, and result in 400 to 500 deaths. From these numbers, fatal cases would equal 0.01 percent to 0.017 percent of the total reported infections.

“Measles was a deadly disease, but particularly in populations of people that are malnourished,” said Morens. In the modern era, however, “measles was of moderately low fatality, around 1 or 0.1 percent.”

Those numbers have decreased dramatically since the vaccine was introduced in 1963. Measles was eventually declared eliminated from the United States in 2000, due to a vigorous vaccination program.

In comparison to COVID-19, measures against measles were relatively mild because the disease was extremely common in society, and the virus’s built herd immunity has allowed for the spread of the disease to be manageable.