By Olivia Green

In July 2021, President Biden claimed that social media platforms were “killing people” by facilitating the spread of vaccine misinformation. Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell cosigned the statement declaring that misinformation is to blame for low COVID-19 vaccination rates.

The debate that followed brought up questions surrounding the public’s belief in vaccine misinformation. Is online misinformation the main catalyst for vaccine resistance?

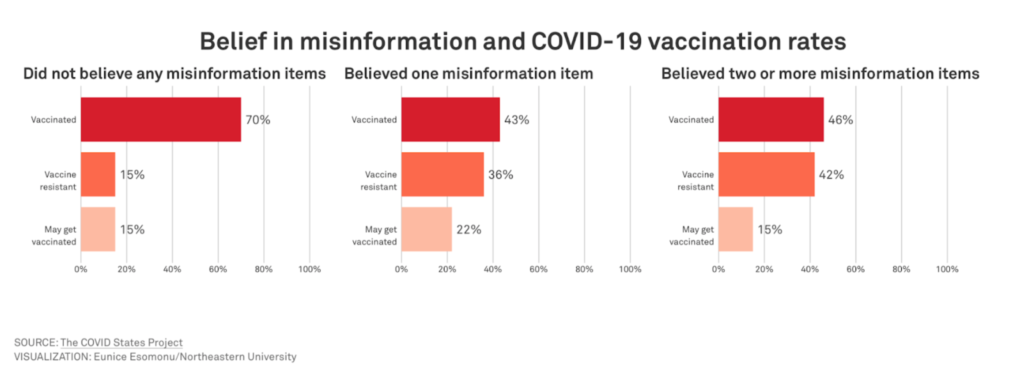

A study led by Northeastern University explored the link between online misinformation and vaccine holdouts. They presented respondents with fake, but popularly circulated claims about COVID-19 vaccines. More than half of surveyees couldn’t say all claims were false. Those who believed at least one claim were less likely to be vaccinated than those who believed none.

There is a strong association, but they cannot definitively determine cause and effect between believing misinformation and being vaccinated, says David Lazer, researcher and professor at Northeastern University.

As of Feb. 2022, CDC data shows that 75.3% of the United States population has at least one dose of a Coronavirus vaccine. Despite the increase, rates remain uneven. Women, African-Americans, and Caucasians with lower socioeconomic statuses are least vaccinated.

An NPR analysis found that vaccine distribution centers, especially in Alabama, Texas and Louisiana, were absent in Black communities, while most white neighborhoods had one. The University of Pittsburgh found that Black people in counties around Atlanta, New Orleans and Dallas have longer driving distances to vaccine centers than white counties.

The fact that vaccine registration is largely online may be to blame, as there is often a racial and economic gap in who has reliable internet access. In Washington, D.C., signing up virtually made it simpler for wealthier, white people hindering Black people from getting appointments.

George Jones, whose nonprofit Bread for the City runs a medical clinic, told the New York Times that hardly any of the people coming in for shots at his clinic were regular patients.

“Suddenly, our clinic was full of white people,” said Jones. “We’d never had that before. We serve people who are disproportionately African-American.”

Vaccine hesitancy is more complicated than fake news. For example, the fake claim that vaccines cause infertility may be the cause of hesitancy in some women; however, it cannot be cited as the primary cause for any demographic.