By Trevon Patterson

The facts, they say, don’t lie. These are the facts:

Breonna Taylor was killed when Louisville police officers broke down the door of her apartment, her boyfriend fired a shot in their direction, and the police responded with a hail of bullets, one of which ended her life. Kentucky’s attorney general presented the case to a grand jury, but no one was charged for Breonna Taylor’s death.

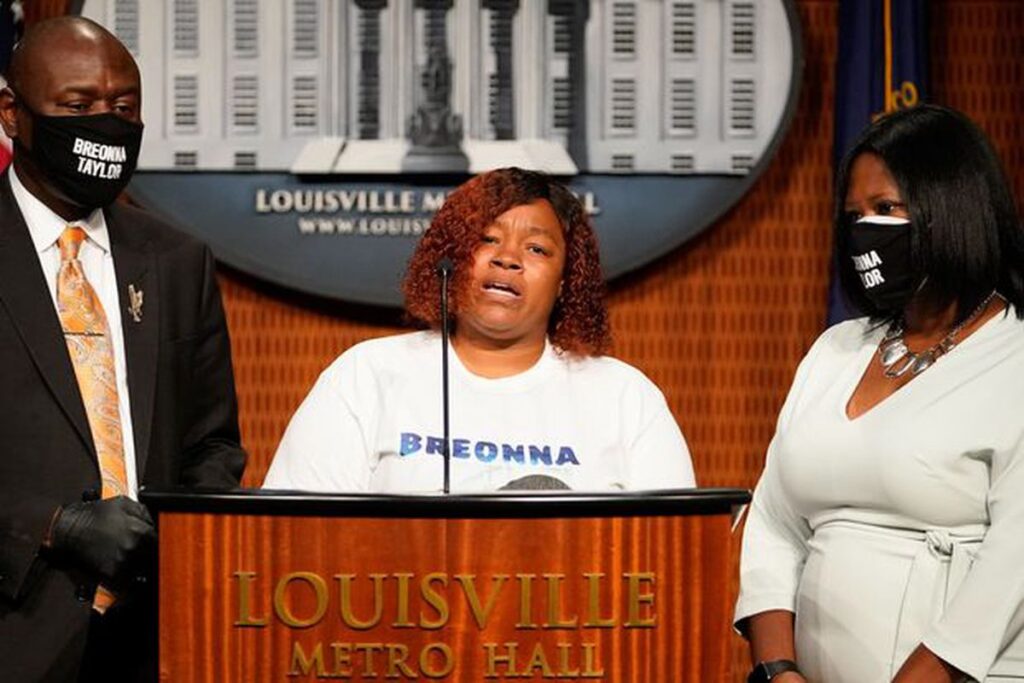

Her mother, Tamika Palmer, asked the state to appoint another prosecutor to examine the facts. “The Attorney General’s unwillingness and refusal to prosecute Breonna’s case, despite grand jurors confirming that they found probable cause to indict the officers on multiple offenses, calls into question whether we face a ‘stacked deck’ when the perpetrators are members of law enforcement,” her formal request read.

The Kentucky Prosecutors Advisory Council said it did not have the authority to do what she asked. Her lawyers are considering challenging that opinion in court. Shortly before Christmas, she also asked President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr. to launch a federal investigation into the death of her daughter and other Black Americans killed by police.

Accountability for police officers who kill seemingly innocent persons is a recurring and deeply troubling concern for the families of the victims, and for many supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The Taylor case provides an opportunity to look more closely at one of the core elements of the controversy: the relationship between facts of life and death, on the one hand, and conclusions of current law, on the other.

Questions remain over whether the officers properly identified themselves before breaking down the door of Taylor’s apartment shortly after midnight March 13, and The New York Times has reconstructed the entire incident, based on court documents, interviews and available video footage.

Yet, there is little disagreement on what happened immediately after the door came off its hinges, and two of the seven officers outside of it stepped into the apartment hallway.

- Kenneth Walker, the boyfriend, was inside with Taylor. Walker said that when he heard pounding on the door, he feared that a former acquaintance of Taylor might be trying to break in, so he fired a single shot toward the doorway. That shot struck officer Jonathan Mattingly in the leg. Mattingly fired six shots in return.

- Myles Cosgrove, the second officer in the hallway, also shot back. Cosgrove fired 16 shots. An FBI ballistics analysis determined that one of those shots was the fatal one, and a Jefferson County medical examiner concluded that Taylor likely died within a minute of being hit by it.

- A third policeman, Brett Hankison, fired 10 shots into the apartment from outside the building, and all through sliding doors and a window of the ground-floor apartment that were covered by blinds or curtains. Those shots struck no one, including three people in another apartment, where some of the rounds landed.

The Louisville police department dismissed Hankison in June, saying he had violated department policy on the use of deadly force by “wantonly and blindly” discharging his weapon. Mattingly and Cosgrove remained on the force, but were assigned to administrative duties.

This week, the interim police chief notified Cosgrove that administrative procedures were underway to fire him. Walker, the boyfriend, who legally possessed the gun he fired, initially was charged with assault and attempted murder of a police officer, but those charges were dropped.

Most state laws give persons an unbridled right to use lethal force in self-defense against intruders. This concept is often referred to as the “castle doctrine” in a nod to a tenet of common law that declares one’s home to be one’s castle. By that logic, Walker had the right to shoot when and as he did.

But Kentucky law does not allow persons to harm police officers, even if the officers’ actions are the reason the person reacts in his or her own self-defense. “Most states don’t allow someone to claim self-defense when they are an aggressor,” Seth Stoughton, a University of North Carolina Law School professor, told The Guardian. “But most states also say that when police are acting in their official capacity they can’t be aggressors for purposes of self-defense law.”

Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron served as special prosecutor in the Taylor case. Under his direction, the grand jury charged Hankison, whose shots had gone into the neighbor’s apartment, with three counts of first degree wanton endangerment, which are felonies under state law. Hankison has pleaded not guilty. But neither of the other two officers was charged.

“According to Kentucky law, the use of force by Mattingly and Cosgrove was justified to protect themselves. This justification bars us from pursuing criminal charges in Miss Breonna Taylor’s death,” Cameron said at a press conference.

“My job is to present the facts to the grand jury, and the grand jury then applies those facts to the law,” he said. “If we simply act on emotion or outrage, there is no justice. Mob justice is not justice. Justice sought by violence is not justice—it just becomes revenge. And in our system, criminal justice isn’t the quest for revenge. It’s the quest for truth, evidence and facts, and the use of that truth as we fairly apply our laws.”

Months of protests demanding accountability had preceded Cameron’s announcement, and in the week before, the city had agreed to settle a wrongful death civil suit with a $12 million payment to Taylor’s family, but no acknowledgment of wrongdoing. There were six possible homicide-related charges under state and federal law . Why were none brought?

“It’s a simple and important question,” Marc Murphy, a local defense lawyer, asked in a newspaper article. “Were the grand jurors asked to consider charges, including the alleged justification, against those two officers? Or did the AG remove them from play on his own? Did the grand jury have the opportunity to decide whether the bullets rained upon Breonna Taylor—one of which killed her—were justified?”

Attorney General Cameron said the grand jury had been given all of the relevant evidence to consider, but a pair of grand jurors, not publicly identified, disagreed. Their comments and subsequent requests from family attorneys prompted local courts to order the release of records from the grand jury’s proceedings. Those disclosures led to the mother’s request for a new prosecutor.

The concept underlying the castle doctrine, which gave Walker the right to use deadly force in self-defense, also is part of the rationale behind so-called “stand your ground” laws, which figured into the legal wrangling following the shooting deaths of Trayvon Martin in 2013, and Armaud Arbery in February.

The laws effectively define the perimeter of the “castle” in the castle doctrine as the reasonable space, or ground, around a person who feels under attack. They grant that person a legal right not to retreat from danger—which would be obligatory under some laws—but instead to stand that ground and use whatever force necessary in self-defense.

George Zimmerman, the neighborhood watch coordinator who shot and killed Trayvon Martin during a scuffle in an Orlando suburb, initially considered invoking immunity from prosecution under Florida’s stand your ground law. Zimmerman’s lawyers later abandoned that approach. He subsequently was tried and found not guilty of second degree murder and manslaughter.

Even though the stand your ground law was not the basis of Zimmerman’s defense, the judge in the case made reference to it in the instructions to the jury, and jurors discussed the law’s rationale during their deliberations. Outrage over the incident and the outcome of the trial launched the Black Lives Matter movement.

Arbery, a Black man, died in Brunswick, Georgia in February. A White father and son said they suspected him of a break-in, chased him down in their truck, and confronted him. In an ensuing scuffle, one of them shot and killed him.

The two White men initially “gave statements to the police in line with the reasoning of the state’s ‘stand your ground’ law” and were not immediately charged, NBC News reported. After a video of the incident was made public, however, the two were indicted on charges of murder and assault. The case has not yet come to trial.

Robert Spitzer, a political science professor at the State University of New York at Cortland who has studied the results of cases in which the stand your ground defense is involved, told NBC News that in one of every three instances in which someone Black is killed by someone White, the killing is ruled justifiable. When the circumstances are reversed and the victim is White and the perpetrator Black, the death is determined to be justifiable only one of every 33 times.

“That’s the reality,” said Spitzer, author of the book “Guns Across America: Reconciling Gun Rules and Gun Rights. “It’s not just how it looks.”