By Arthur Cribbs

Victorious plaintiffs in a lawsuit to compensate Maryland’s four historically black public colleges for years of inequitable funding have criticized as “disingenuous” Gov. Larry Hogan’s claim that the state cannot afford to do so because of the financial toll of the coronavirus crisis.

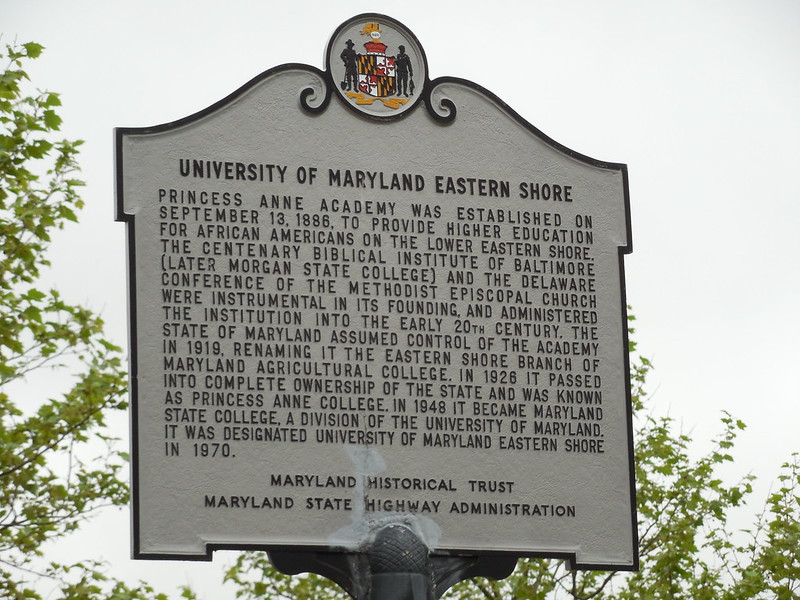

In March, the General Assembly authorized a 10-year, $580 million spending plan that would boost student financial aid, help recruit and train faculty, and better promote under-enrolled programs at Bowie, Coppin and Morgan state universities, as well as at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore.

In early May, however, Hogan announced that “the economic fallout from this pandemic simply makes it impossible to fund any new programs, impose any new taxes, nor adopt any legislation having any significant fiscal impact, regardless of the merits of the legislation.”

Maryland state government was forecast to lose as much as $1.2 billion in revenues as a result of the crisis. The state has received $1.3 billion from the federal coronavirus relief fund, but the governor’s office said that money can be used only for pandemic-related expenses.

A first payment to the universities could have been included in the $47.9 billion state budget for the new fiscal year, which began July 1, but was not.

Michael D. Jones, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, noted that Hogan had said last September—months before he announced the veto and months before the virus began to spread—that he was unwilling to allocate more than $200 million.

“It is disingenuous to now claim that the state cannot afford to remedy this decades long racial disparity because of the pandemic,” Jones told diverseeducation.com. “There isn’t a recession exemption to a constitutional violation.”

State Sen. Charles E. Sydnor III, a Baltimore County Democrat and key sponsor of the legislation, said the money would “provide critical resources to our HBCU pre-med programs, as well as Morgan’s public health program, Coppin’s and Bowie’s nursing programs and the pharmacy and other health-related fields at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore.”

“All of these academic programs are critically important to addressing the underlying health disparities laid bare by the COVID-19 crisis,” Sydnor said.

In recent years, several state governments have acted to help historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) overcome vestiges of racially segregated public systems of higher education. Maryland was poised to join them.

Then Hogan made his announcement.

“We are frustrated and disappointed that our work was responded to with the Governor’s veto,” Del. Darryl Barnes, a Prince George’s County Democrat and the head of the Maryland Legislative Black Caucus, said at the time. “Allowing the bill to become law would have leveled the playing field for our HBCUs.”

The legislation passed both houses on veto-proof majority votes. The General Assembly is scheduled to return in January, at which time it could override Hogan’s decision.

A coalition of HBCU alumni and advocates filed suit in 2006, accusing the state of effectively undercutting the lure of some signature programs at the historically black schools by providing state funds to replicate those programs at predominantly white schools.

The U.S. District Court ruled in 2013 that while the HBCUs were not deliberately underfunded, such practices effectively nurtured inequality. The plaintiffs proposed spending $577 million to settle the case.

House Speaker Adrienne A. Jones introduced the bill that eventually passed, saying that the stalemate over funding had “lingered for far too long, and is a blemish on our state’s strong system of higher education.”

Del. Jones, a Baltimore County Democrat, last year became the first woman and the first African American to be elected speaker. Both the House and the Senate have Democratic majorities.

The party’s strength is based in the urban and suburban areas of Baltimore and in Prince George’s and Montgomery counties the eastern and northern flanks of the District of Columbia—communities with substantial black populations that include many HBCU alumni.

The vote in Maryland came as both public and private HBCUs nationwide have been struggling with uncertain federal funding, sputtering enrollment, and relatively small endowments. Many of their students are disproportionately burdened by loan debt, and come from families with unsteady financial fortunes. The economic impact of the pandemic worsened those problems.

Publicly-supported HBCUs like Maryland’s have fared better than their private counterparts in some fiscal affairs, while still encountering what some characterize as new forms of old problems.

“In Maryland, programs were being copied from HBCUs to nearby predominantly white institutions, therefore diluting the ability of HBCUs to draw students,” John M. Lee Jr., former vice president of the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities, said in a telephone interview.

For instance, the University of Maryland Baltimore County and Towson State University, both predominantly white schools, had established a joint Master of Business Administration program. That program ended in 2015 after criticism that it competed unfairly against a similar program at Morgan State, an HBCU in the city of Baltimore.

Towson State introduced a computer science master’s program similar to one at Bowie State, an HBCU in Prince George’s. Enrollment in the program at Towson increased from 23 students in 1994 to 101 in 2008. During the same period, enrollment in the Bowie State program fell from 119 to 29.

Duplicate programming also has been a central issue in South Carolina, where five years ago, legislators hinted that the state’s only public historically black university might need to close because of too much debt and too few students. The real problem, according a lawsuit still pending, has been too little state money.

Alabama agreed to grant its two historically black public universities more than $200 million for capital projects, scholarships and new academic programs. The appropriation was the result of a lawsuit that claimed discriminatory state funding in decades past.

In Mississippi, lawmakers acknowledged the state’s lesser financial support of its three historically black public colleges. In 1992, it approved spending more than $500 million over 30 years to compensate Jackson, Alcorn and Mississippi Valley state universities.

David Burton, president of the Coalition for Equity and Excellence in Maryland Higher Education, a plaintiff in the current lawsuit, cited the Mississippi situation in a criticism of Hogan’s explanation for denial of funds.

“An economic downturn that disproportionately hurts black communities is precisely the time to help black colleges out of the hole the state dug. Instead the governor cut the lifeline extended by the legislators,” Burton wrote in an opinion article in The Baltimore Sun.

“Even Mississippi recognized that economic downturns are no excuse for ducking constitutional responsibilities. It began its larger HBCU settlements during the 2001 recession, and continued them during the Great Recession of 2008-09.” Jones, the lawyer in the lawsuit, and Earl Richardson, president emeritus of Morgan State, co-authored the article.

Despite Mississippi’s commitment—which would amount to more than the $580 million approved in Maryland if inflation were considered—its HBCUs still wrestle with enrollment problems, including some related to deficiencies in K-12 education in predominantly black regions.

In 2016, half of all black students in Mississippi attended schools in a district with a D or F rating on the state’s annual A-F rating scale. Among schools in F-rated districts, more than 95 percent of the students were black.

Racial disparities in education are not as glaring in Maryland as in Mississippi, although inconsistencies between students of color and white students persist in certain counties.

In Montgomery County, one of the state’s most affluent, fewer than half of the black and Latino kindergarten students reached the school readiness benchmarks, while more than 65 percent of Asian and white students in the same district did.